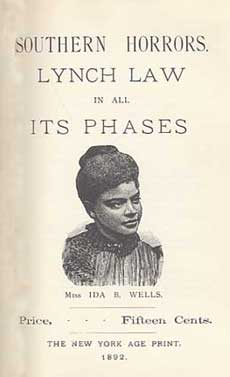

Before I came across Ken Gonzales-Day's work, specifically his work in Erased Lynching, I thought that the historical weight of lynching was only located in the south where hundreds of Black bodies were targeted because of racist ideologies that became fused with law, sexuality, and the policing/criminalizing of (certain) bodies. This history, much documented by the late Ida B. Wells-Barnett in Southern Horrors (1892) and A Red Record (1895) is more known in our national discourse. When it came to terrorizing communities of color with that practice, Ken Gonazales-Day brings to light this historical significance in our own Californian backyards; the history of lynching in the west.

Ida B. Wells, Southern Horror. Lynch Law in All Its Phases, 1892

Ken Gonzales-Day, Lynching in the West, 1850-1935, 2006

Gonzales-Day, a current Professor at one of our very own Claremont Colleges, Scripps College, has documented these stories in a very critical way that acknowledges different parts of our history as community residents of the Inland Empire. Less known is how Latinos, Asian Americans, and Native Americans were largely targeted in the west, especially in California. Although a majority of the cases that Gonzales-Day documents largely occur in the northern California and in the Los Angeles county, there are a few cases which occurred within our communities. On July 6, 1878 in the county of Riverside Refugio Boca, of Mexican origin, was alleged of committing murder and was therefore sentenced (p. 224). Along with his story there are countless others from neighboring Inland Empire communities that he documents.

Gonzales-Day’s scholarly work of documenting that history is expanded with this photographic work in both of his projects, Erased Lynching and Hang Trees. Specifically in his work in Erased Lynching, he consciously removes the bodies of the numerous victims who were lynched in the west while keeping the rest of the image the same. The powerful thing that comes out of this is that the viewer’s gaze then falls on the perpetrators; it illuminates those who perpetuated the institution/practice of lynching on Latino, Native American, and Asian American communities in California.

East First Street (St. James Park), 2006

3.7 x 6 inches

Lightjet mounted on cardstock

Ed. of 6

Disguised Bandit, 2006

3.8 x 6 inches

Lightjet mounted to cardstock

Ed. of 6

Tombstone, 2006

3.7 x 6 inches

Lightjet mounted on cardstock

Ed. of 6

The viewer therefore begins to gaze the crowd who attended the event instead of the mutilated body that was once there. Gonzales-Day denies the viewer the voyeuristic pleasure of gazing at the body; he limits the gazing violence that is placed upon the victim’s body and spirit. By erasing the bodies he does not erase this history, but instead allows us to see the image as part of a larger institutional force that perpetuated the social practice of lynching. The viewer therefore shifts their gaze unto what would traditionally seem invisible: the structural and social forces that sustained this practice against Black/Brown/Yellow/Red people and communities.

I encourage you to not only check out Gonzales-Day’s work on his website, but to also check out his research in Lynching in the West, 1850-1935. As both an artist and a scholar he is able to complement his photographic work with his scholarly research, allowing his audience to view the complexity of this history. His photographic work pushes us even further to begin to shift the way we viewed and framed the systemic violence of lynching that was directed at different communities. As residents of the Inland Empire, or of any community in general, it is always important to be aware of the (her/his)stories that are embedded in this area. This will not only help us understand that artwork of certain IE artists, but also understand how we fit into the larger, macro picture of the social fabric.

No comments:

Post a Comment